Greenpeace journeyed to Antarctica on the Arctic Sunrise, carrying a small but might two-person submarine called the DeepWorker.

Our mission was to build support for ocean sanctuaries, the best tool there is to protect marine biodiversity, rebuild depleted populations and give our oceans a fighting chance to survive the damage humans are causing from climate change, overfishing and plastic pollution.

This year we expect the United Nations to finalize negotiations on a Global Ocean Treaty. If we are successful, it will allow us to scale-up sanctuary protections for the first time, growing from 2 percent of the oceans currently protected to 30 percent by 2030.

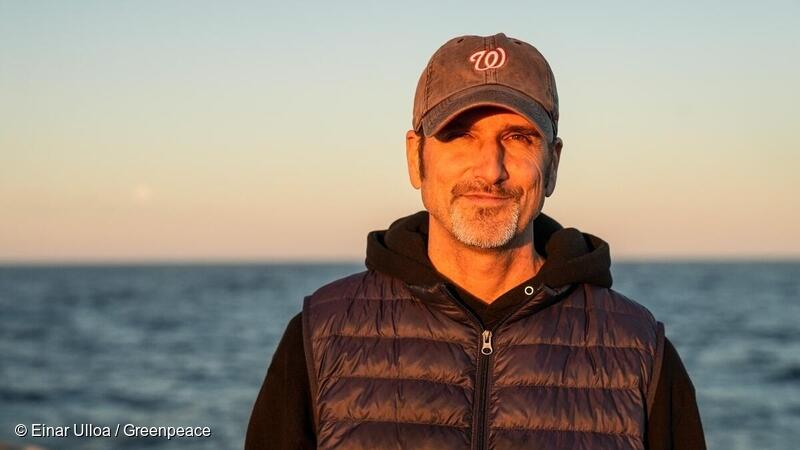

Explorer, marine biologist and Greenpeace USA Oceans Campaign Director John Hocevar is on board and sharing his diary of the journey.

February 10, 2022

After all the planning and a roller coaster ride of good news/bad news/terrible news/it-seems-like-good-news but I don’t trust it anymore, I traveled to Punta Arenas, Chile, where I will board the Arctic Sunrise and leave for Antarctica after a week of quarantine.

There is nothing like wearing an n95 mask for 31 hours to renew your appreciation for everyone who has to wear these things every day. OMG.

I arrived in Santiago already tired, after spending the 10-hour flight from Atlanta watching movies instead of trying to fold my body into a shape that could have conceivably gotten a little sleep. I was sitting in the airport with the science team when Coca-Cola called. They wanted to give us a heads up that they were committing to make at least 25 percent of their beverages in reusable packaging by 2030. This is the first reuse commitment of its kind from a big brand, the direct result of people the world demanded they do better.

We have work to do to hold Coke to this and push beverage companies to completely abandon throwaway plastic bottles. In the meantime, the signal this sends to policy makers and other corporations is going to be very helpful. Huge congrats and thanks to everyone (including so many of you reading this!) that helped make this important step possible.

Time to celebrate!

February 11, 2022

Quarantine, day one. After two years without traveling, it is hard to believe I am here in Patagonia looking out at the Strait of Magellan. I will be in this room for most of the next week, but at least it is a nice view!

Thinking of my partner Victoria back home in DC, who is defending her doctoral dissertation today! So proud. I hate not being there in person, but will tune in via zoom if the Ancient and Powerful Gods of Hotel Internet smile upon me.

February 11, 2022 (Part II)

Wow. I am gone for two days, and the world turns upside down. First Coke announces they are shifting towards reuse, and then today the State Department emails to say they are calling for a binding global plastics treaty that addresses the full life cycle of plastics and will curb plastic pollution at its source. This is a complete reversal from 2020, when the USA’s opposition to any kind of plastics treaty delayed the whole process by two years.

Here’s our response.

And Victoria is now DOCTOR Victoria.

What a day!

February 12, 2022

Quarantining means different things in different circumstances. For us, it means that our international team of friends and future friends do not get to see each other in person, and that we must avoid contact with anyone at all. Meals are delivered to our rooms. We can put on masks and leave the hotel to get some exercise, but cannot go into stores or restaurants.

This is a very windy place, but the weather is a bit warmer than back home in DC, and it has been great to walk along the coast. The beach is pretty rugged, as it was clearly used as a dumping ground for a very long time. There are countless tires, minefields of broken glass, and a soul-crushing amount of plastic trash. And still it is amazing to be here with gangs of imperial cormorants, spongy kelp, razor clams, and the ever-present possibility that dolphins or whales could pop up at any moment.

And today I saw two tugboats!

I really like tugboats.

I also passed by a memorial to Luis Antonio Pardo Villalón, the Chilean captain who rescued the 22 crewmen from Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, after they had been stranded on Elephant Island when the Endurance was crushed in the ice. Shackleton’s determination to get his crew through the ordeal was truly heroic, a story for the ages. And still, you can see how Chileans might say that the real hero was a local captain who set out to rescue a bunch of sailors who were very far from home and perhaps even farther out of their depths.

February 13, 2022

Did I mention Patagonia is windy?

The Arctic Sunrise is over in Ushuaia, Argentina. They should arrive here on the 16th, weather permitting. It is a little hairy out there right now, though, with gale force winds covering the whole region! As Hector (along with Roberto, joining us from National Geographic) said this morning, “If you go for a walk today, put some stones in your pockets!”

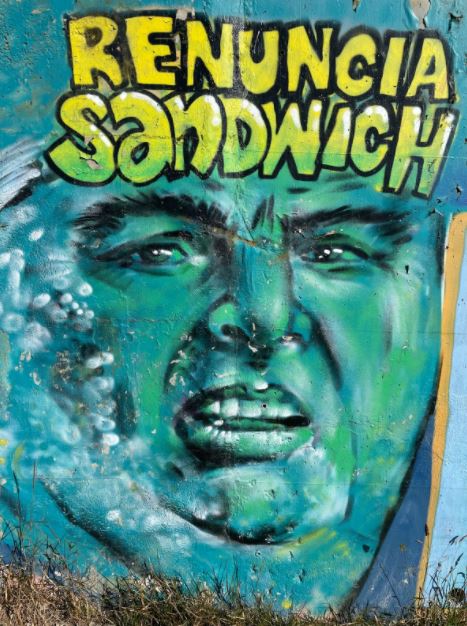

In December, Chile elected a new president, Gabriel Boris, a former student activist from Punta Arenas, soundly defeating President Sebastian Pinera, a conservative billionaire. The election came after a mass social movement demanded that the constitution adopted under Pinochet’s regime must be rewritten.

I have only visited three cities in Chile, but all had a lot of great street art, much of it on the theme of resistance. Here are a few of my favorites here:

February 14, 2022

Happy Valentine’s Day! You know, if you’re into that sort of thing.

You might say that hiking up a five mile “hill” into gale winds so strong they caused a fatal car crash in front of our hotel is a weird choice for an optional solo activity, and, in hindsight, I would not argue with you. But! I may well never pass this way again, and I wanted to see a little of Patagonia so I spent a couple hours hiking up to the Reserva Nacional Magallanes. It is true that when I got there the park was closed, but I did see some rabbits, some raptors that were probably looking for those same rabbits, and some nice rolling hillside with a lot more trees than can be found near our hotel.

I closed a wide open gate just as these horses were about to leave their beautiful meadow for the danger and excitement of the streets. The most daring horse was already halfway out, and the rest of them were watching closely to see what was going to happen next. I hope they know I did it for their own good.

Best of all, though, were the spectacular views of the Straits of Magellan from up on high. I am sorry that I had neither the talent nor the camera to give you a sense of what it was like. You’ll just have to trust me on this.

Plus, the nice lady outside the strip club I passed on the way back down said I was guapo.

Rachel Downey, Antarctic sponge expert extraordinaire, stumbled upon this while out walking today.

Clearly, Chile is rooting for us.

February 16, 2022

The Arctic Sunrise is anchored in the harbor!

The whole team quarantining here at this hotel watched the ship arrive from our separate windows. (Don’t worry, I can’t see it in this picture either.)

February 17, 2022

A nurse has arrived at the hotel to administer our PCR tests in our hotel rooms.

The team’s chat sounds like a horror movie. He is downstairs!

Oh my god, he got Hector and Tim! He’s outside the doo…

In fairness, I should say that Luis Muñoz was kind and very professional.

The subs arrived in San Antonio, Chile by container ship from Vancouver. Then the Nuytco team (Jeff and Jared) had to take them apart and repack them so they were shorter and empty of all fluids.

The subs were trucked to the Santiago airport, and put on a plane last night. They arrive in Punta Arenas this evening, and we will start loading and reassembling tomorrow. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that Chilean customs opened up EVERYTHING in the container, and confiscated a lot of what is needed to make the subs work. So today the team will be scrambling to try to replace everything.

Argh!!!

February 17, 2022 (The uh-oh Remix)

Four of us just got back positive results from our PCR tests, myself included. All of us have been extremely careful, so we hope that it was a false positive. We can re-test in two days, and if we are clear we will be able to leave as soon as the ship is ready. If not… Chile requires 7 days of quarantine after a positive test. We are trying to stay positive, but this is not good news.

February 19, 2022

The last few days, no longer able to leave our rooms and worrying that our positive COVID status could delay the whole expedition, have not been much fun. A camera would show a very goofy montage of reading (I finished Neal Stephenson’s new 700 page cli-fi novel), working, and moving tables and chairs around in a desperate attempt to get a little exercise. The soundtrack included 80s metal (Voivod), punk (Dillinger Four, Bad Brains, Neon Bone) and country (Dwight Yoakum, Sarah Shook). And a lot of texting among the four of us, trying to stay positive about being negative for our next COVID test.

February 20, 2022

We got our second PCR test results back, and are all negative!

Now we just need to wait to see if the Chilean authorities will clear us to leave, or if we need to wait four more days. The ship will leave either way tomorrow, so we would need to wait to join them later. Not ideal, because we all have a lot to do on board to get ready to start diving, but at this point it feels like we are in pretty good shape no matter what.

February 21, 2022

The Sunrise is anchored right in front of the hotel, where we have spent much of the past week and a half looking out our windows. We have seen a rock concert, storms, sunshine, wind storms so severe they caused a fatal car crash, dolphins, and even whales.

February 21, 2022

And we have news! We are cleared to join the ship, and will leave today for Antarctica! A beautiful day to start our four day voyage south. Hopefully our trip across the Drake Passage will be a bit less rough than last time, which tested us all. Even the seasoned sailors were exhausted, having to work double time to cover for everyone who was stuck in their bunks. The waves were so intense that the rolling of the ship caused whole shelving units and even the washing machines to break their welds and rip off the walls.

But first, we will have a calm and beautiful trip through Patagonia, escorted by a pod of Commerson’s dolphins riding the bow wave.

February 24, 2022

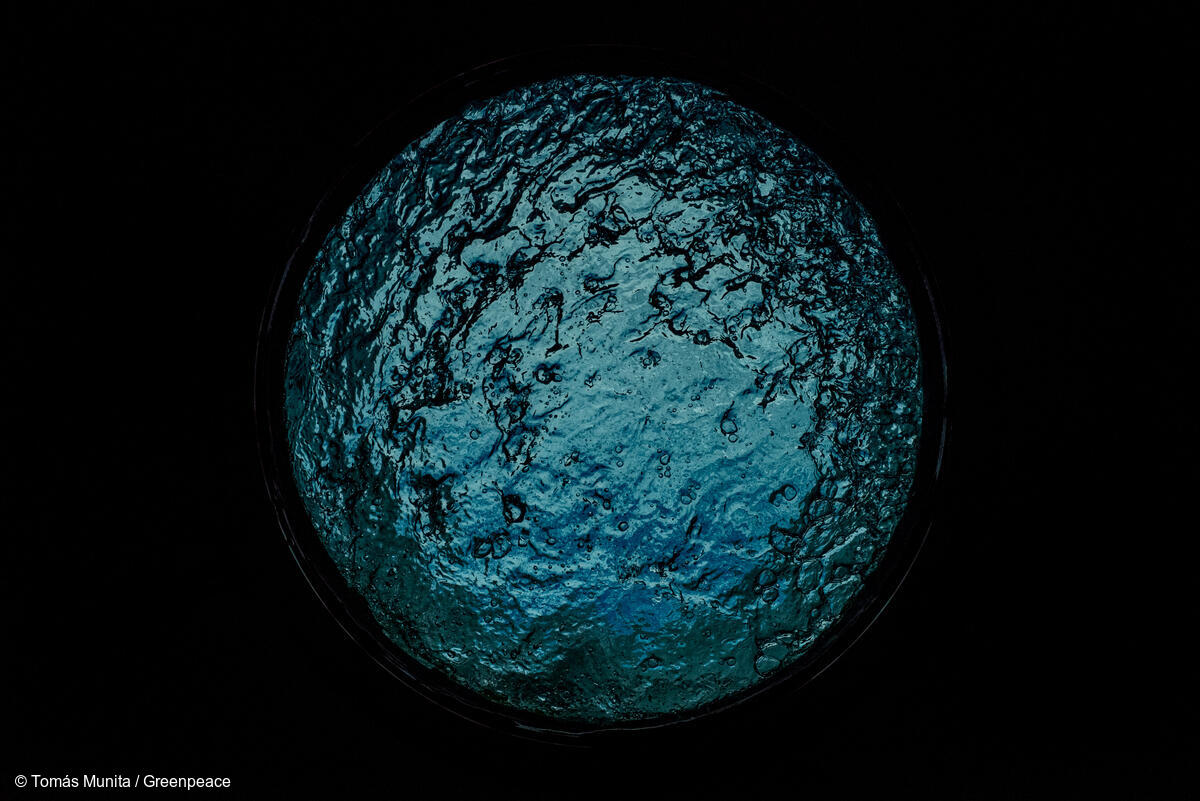

It all started so peacefully! But then we hit the Drake Passage, on a round-bottomed ship with no keel that is built to handle sea ice but can be tough on the people on board. Famously and sometimes affectionately known as the Washing Machine, the Arctic Sunrise is the ship I love to hate in moments like this. And with the Drake, the moment lasts for three days. The Drake was relatively calm for this crossing, but in a way that somehow felt worse than ever.

By yesterday afternoon, there was more water leaving the deck than washing onto it. But it wasn’t until this morning that I felt up to opening my laptop.

^ Sea water seen from a porthole onboard the Arctic Sunrise during heavy weather conditions in the Drake Passage.

February 24, 2022

Today we woke up to the news that Russia has invaded Ukraine. This is the first expedition I can remember where there were no Ukrainian crew members with us, but most of us have friends there we are trying to check in with. And, of course, the implications are bigger than Ukraine alone.

We are heading for an area designated by the Antarctic Treaty as a zone of peace. Peace is in our name and our mission, our history and our responsibility. As with billions of people around the world today, those of us on board are feeling far from Ukraine – but the people of Ukraine are very much in our thoughts.

We stand, as always, for peace and justice.

And we have arrived. Hawthorn Island is calm and stunningly beautiful, with black rock outcrops, snowy peaks, and small ice bergs all around. The icebergs are constantly crackling and popping as air bubbles are released, making it sound like we are surrounded by a chorus of ice singing to us in an alien language. The seals (looking for all the world like they are lounging in the bath) and penguins probably understand it perfectly. We will anchor here tonight, and transit to Livingston Island to test dive the sub tomorrow.

February 25, 2022

Now that we are through the Drake Passage, there is lots to do to get everything ready to dive.

This is a bit more involved than usual, as the Nuytco team had to dismantle the subs in order to transport them to join the ship in Punta Arenas. Everything must be tested, and not everything works the first time around. Once we get to the point where it seems like everything looks good on deck, we’ll do a couple practice runs putting the sub in the water with the crane without anyone inside.

If that goes well, Susanne (Dr. Lockhart, our lead scientist) and I will go down to test the rest of the systems. A lot has to go right for us to be successful here, so this is one of the most stressful parts of the whole expedition. The Nuytco team can fix just about anything, but there’s always the chance that there is something broken that cannot be fixed out here on our own.

And… our test dive was a success!

The crew very quickly became expert at safely maneuvering the sub across the deck and over the side with the crane and four taglines to keep things under control even on a rolling ship. For them, it is a different shape, but nothing particularly challenging – they do the same with our Rigid Hulled Inflatable Boats (RHIBS) all the time. Then, after a short dunk while still on the crane to check our buoyancy, we were off.

For the first couple minutes, the water was clear, bright and quiet. Around 200 feet, it started to get darker – still plenty of light above us, but dark below. We kept our lights off most of the time as we descended into the darkness, to conserve our batteries and to watch out for bioluminescent creatures that flash, glow and pulse to attract mates, distract predators, or attract prey. We slowly dropped down to the bottom of Half Moon Bay reaching a depth of about 1525 feet (465 meters).

As expected, it was flat and silty. A good, quiet place for a test dive. But even here, there was far more life than most people would ever imagine. Just above the bottom, there were schools of small silvery fish with mirror-like scales. The seafloor was dominated by invertebrates, though: sea cucumbers, brittle stars, feather stars, worms, anemones, and dozens of other creatures we will need to review the video to identify. We also saw a couple little octopuses, which didn’t seem to know quite what to make of us. It’s possible they were just too busy plotting their takeover to pay us much attention.

And there were sea pigs!

A genus of deep sea cucumbers called Scotoplanes, sea pigs are… well, hard to describe. I think we can all agree that sea pigs are not exactly dolphins or turtles, but they do have their fans. You can watch sea pig cartoons, buy cuddly stuffed sea pigs, or follow them on social media, where they have their own pages. Wired magazine can’t tell if the sea pig is adorable or terrifying. The Monterey Bay Research Institute has reviewed the best available science and concluded that sea pigs are weird and wonderful.

Which is the correct answer, obv.

February 26, 2022

Last night, we headed south into the Weddell Sea. From the bridge this morning, I watched humpback whales, seals, penguins, and orcas. The icebergs are endlessly compelling, with shapes and colors that exist nowhere else. Forget snowflakes – these are building sized sculptures, each one completely unique. There was a meeting about logistics, but who could be expected to focus on mere humans when surrounded by this glorious wilderness?

We shouldn’t be here. As the historian Thomas Henry wrote, “[The} Weddell Sea is, according to the testimony of all who have sailed through its berg-filled waters, the most treacherous and dismal region on earth.”

We should not be seeing expanses of open water. But there is less ice in Antarctic waters than at any time in recorded history. Since the record was last broken in 2017, the region has lost an area of sea ice roughly the size of Pennsylvania or Switzerland.

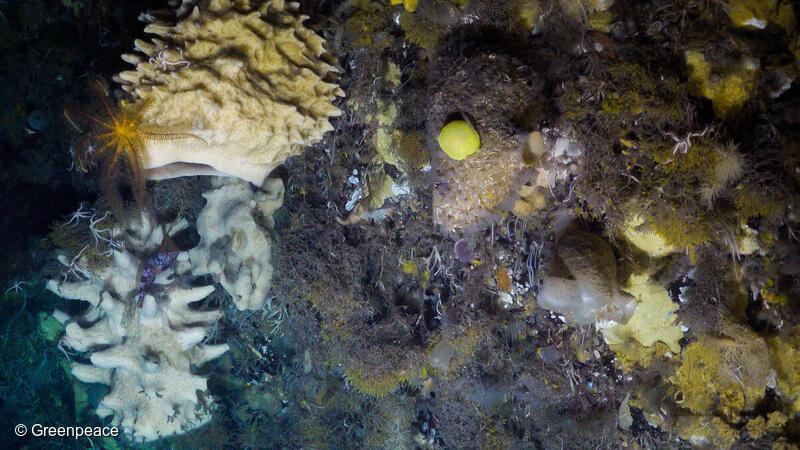

Today we dove in Erebus and Terror Gulf, off the coast of James Ross Island, which was completely inaccessible the last time I was in Antarctic waters with Greenpeace, in 2018. We were down for over three hours, and the sub worked perfectly. We did a long video survey of the seafloor, which was relatively flat and silty but full of life. There were so many soft corals that it reminded me of a meadow at times, and some areas populated by elephant ear sponges sticking up to filter plankton and bits of food as it sailed by in the current. There were hundreds of ice fish, including some in nests similar to what was recently reported in another part of the Weddell Sea.

We collected several specimens for the science team, including a coral relative called a candelabra that is so rare that there has been little written about them since the early 1800s. Collecting specimens involves using a joystick to maneuver a hydraulic robot arm, and I am terrible at it. Clearly, I should have spent more time playing video games as a kid. I am the kind of person that will carry the spider outside rather than squash it, so I don’t love this part of the job – but it is important, both for science and for conservation. The difference between collecting things with the sub, where we can take a small portion of a specific sponge or coral, and the more common dredges or trawls, is like night and day.

There has been very little research in this area, so we may see if we can do more surveys before the weather forces us to move on. Even in the silty spot we dove today, which looked like it had been scoured by icebergs or glaciers in recent years, was covered in organisms that are recognized as indicators or a Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem.

^ A Candelabrum collected during a dive in Erebus & Terror Gulf, in Antarctica.

February 27, 2022

All dressed up and nowhere to go!

The crew was ready with four taglines to keep us stable while we are on the crane. The boat was in the water, with Claire kitted up in a dry suit in case she needed to jump in the water to troubleshoot anything. The ship was on location, and Susie and I were in the sub on deck. I was wearing five shirts, thick pants with two pairs of long underwear, a vest, and a jacket, gloves, a wool hat, two pairs of socks and a pair of wool boot liners that look like moon boots. We’d finished our pre-dive checks, and the hatches were closed.

And then the wind picked up, and the ice started to move in.

Abort! Abort!

We will try again this afternoon. Sub life.

Time for lunch.

February 27, 2022 – Afternoon

This afternoon was a bit calmer, and we were able to dive in Admiralty Sound, near Cockburn Island. As we sat in the sub getting ready there were seals playing all around the ship. The dive ended up being a tough one, as visibility was very poor. There was a lot of stuff in the water, which is often referred to as marine snow. Once we got to the bottom, it got worse. The seafloor was covered in very fine silt, and if you even looked at it sideways, you would instantly be blinded, completely surrounded in a giant gray cloud. In between the clouds, we could see that there was quite a bit of life down there, but the visibility was so bad that we couldn’t always really be sure what we were seeing.

When you are exploring new areas for the first time, sometimes what you discover can change the world. And then there are times like this dive, when you just have to admit that there is nothing constructive you can do and call it a day.

February 28, 2022

Today was one I will never forget. We had two successful dives deep into the Weddell Sea, possibly farther south than any research dive in history. We were working below 65 degrees latitude, in an area that would typically be covered by sea ice. Through all the planning for this expedition, none of us dared believe that we would be able to dive a half kilometer deep in such inaccessible waters. But we did dare to give it a shot, and the results were incredible.

Unlike yesterday’s murky and frustrating dive, today we had crystal clear water and remarkably calm conditions. Diversity was surprisingly high, particularly when you consider that for most of these creatures’ existence, the surface has been covered with ice. Until quite recently, scientists believed that these areas would essentially be devoid of life! Instead, we found both variety and abundance. One reason there is so much happening down there is the enormous amount of dropstones, which are rocks ranging in size from pebbles to boulders that were transported out into the Weddell Sea by sea ice, which eventually melted. Once on the bottom, drop stones provide places for marine life to hide. They are also solid places for creatures like corals and sponges to attach to, creating even more three dimensional habitat for other species.

It was an amazing experience to be able to be the first people to ever see these areas in the Weddell Sea today. At the same time, it was impossible to forget that the reason we were able to get here is that climate change is very quickly transforming entire ecosystems. Whether or not our dives today turn out to be record breaking, they are just footnotes on the terrible fact that there is now less ice in Antarctic waters than at any time in recorded history. Since the minimum sea ice record was last broken in 2017, the region has lost an area of sea ice roughly the size of Pennsylvania or Switzerland.

The list of climate impacts reads like something out of the Book of Revelations: fires, floods, storms, plagues, droughts, pestilence, wars… To adapt a phrase from one of my favorite authors, William Gibson, climate change is already here. It is just not evenly distributed. The impacts have begun, and will continue to get worse. The question now for humanity is very simple: will we do what the science tells us is necessary, and move away from fossil fuels, reduce meat consumption, etc., or will we consign our descendants to a planet that is no longer livable?

When I woke up this morning, I saw a post from an artist friend who was talking about how it feels to be spending her days making paintings of birds while not far from her home birds were dropping from the sky in flames due to forest fires. Then at breakfast, Tim, the polar guide on this expedition, told me that he’d been up half the night checking in with his family in New South Wales, Australia, where there are record floods. His sister had to be rescued from the roof of her home.

While the sub was dangling from the crane at the end of the dive, Susanne and I watched whales that had apparently passed right by the sub while we were coming up. We talked about the incredible amount of life we’d just seen at the bottom of the brutally cold Weddell Sea, and how our findings would inform scientists’ understanding of the ecosystem here. Above all, as the entire region changes almost in front of our eyes, it is a stark reminder of what is at stake. This is a place, and a planet, worth fighting for.

March 1

It is almost 9 pm, and I am still so wound up about this afternoon’s dive that I am practically vibrating. I can’t wait for people to see footage from this one – truly one of the most spectacular dives of my life. We were on a vertical wall, with almost perfectly clear water. Most of the dive was below 1700 feet (520 meters), and it was so cold that the condensation inside the sub froze. The wall was so covered in sponges and corals that the corals were blocking the lights and creating shadows when we were trying to film the octopus, which was so big it wouldn’t all fit in the frame until I backed up the sub. There were feather stars, and snail fish, and it was all so incredible that I was relieved to realize that my mic wasn’t recording because I’m pretty sure all I could manage was to exclaim “this is nuts!” over and over. I am sure that the evidence from this dive will lead to this site being protected as a Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem.

By the time we finally came up, icebergs had moved into the area so we had to do some real maneuvering to find a clear place to surface. The RHIB towed us back to the ship so we didn’t have to run down our batteries any more than we already had.

What a day!

March 2, 2022

Good dive today in a deep canyon in the Bransfield Strait. I was excited about this one – two previous expeditions in the Bering Sea had taught me how unique and impressive underwater canyons can be. We dropped onto a fairly flat seabed, which was momentarily disappointing before we realized the slope was just behind us. We descended to 543 m. As we’ve found a couple times now, the ship had a difficult time tracking us once we got much below 500 m. This isn’t usually an issue, so our theory is that there is a band of water so cold and dense it is interfering with the signal.

We were still able to survey a pretty good section of the sea floor, and once again saw large numbers of the types of habitat-forming invertebrates that are classified as indicator species of Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems: plenty of corals and sponges, as well as large anemones, bryozoans, and others. I used the robot arm to collect a delicate lace coral, which was unusually abundant, and a small cup coral that we’d been looking out for. After dozens of dives and a half dozen expeditions with the sub, I’m finally getting the hang of using the arm.

Electric vehicles are in the news a lot these days, for good reason. The sub is my favorite EV – it runs on rechargeable batteries that usually give us close to four hours of operation. We pushed the batteries really hard yesterday on the wall dive, so all of us were watching them closely today to see how well they recovered. It was a little nerve-wracking, as there was a real chance that we’d damaged them in a way that could impact the rest of the expedition. The batteries performed perfectly, so we are in good shape.

Meanwhile, the weather, which has been so kind to us so far, is threatening to turn. Fingers crossed we will be able to get in a few more dives before we have to head to Ushuaia, Argentina, for our next mission.

March 3, 2022

Very solid dive – a steep slope, with parts fully vertical. It was an odd mix of rock and soft sediment, which I don’t usually see on such a steep location. It was a bit tricky to pilot the sub here, as the wall was constantly changing direction so I had to do the same to keep us close to the substrate. And, as we’ve seen several times now, the current was flowing along the slope in what seemed to be an inconsistent direction. It was beautiful, and we got a lot of good work done. We won’t know until the video is processed, but I think we were able to get quite a few nice close ups of sponges, corals, anemones, and feather stars.

I used to believe that nothing could compare to tropical coral reefs when it comes to the amount and diversity of colorful, living creatures. On a healthy coral reef, you might find corals covering 40% of the reef. There will also be many other types of animals and plants competing for space on the reef, and there is really no such thing as bare rock unless something has just been eaten or dislodged. We have seen similar things in the cold, dark depths of Antarctica. All of the species are different, of course, but just like on a tropical reef, there is very little barren substrate. For much of the dive, it looked like living creatures covered 90% of the available surface.

This is why we are here. We want to change the way people think of our oceans. I’ve fallen in love with each part of the ocean I’ve ever had a chance to get to know. They were all different, but they were all full of life. From the Long Island Sound tidal pools and estuaries near where I grew up to the Florida reefs I studied in grad school, and from the Arctic to the Antarctic locations I have explored with Greenpeace, I have always found surprises and wonders.

We protect what we love.

March 4, 2022

In the morning, Susanne and I dove the soft slope of Vega Island, which was one of the prettiest sites so far. It wasn’t as completely covered with large colorful invertebrates as some of the places we have surveyed, but there was still a lot going on. Where things got really wild were the drop stones, often the size of large boulders. Each drop stone was like a creature condo, with no vacancies available – every inch was covered with animals, and usually there were more animals perched on top of those animals. It seemed like each bottle brush coral was host to at least a half dozen sea cucumbers.

This afternoon was the first dive with Rachel Downey, an expert on Antarctic sponges. We have been seeing SO MANY SPONGES on these last few dives, so I have been dying for her to see this. We dove on a steep wall off Corry Island. As we sat in the sub running through our pre-dive checks, we were facing the stunning sheer black cliffs of the island, which we knew continued down to at least 700 meters below the surface. We haven’t seen many penguins lately, but humpbacks are always close by.

The dive did not disappoint. It was so steep that we couldn’t drop onto the bottom, because the bottom was more like a wall. Instead, we dropped down to 1500 feet, and then headed for the island. When we reached the wall, it was covered with orange and yellow feather stars. From my standpoint piloting the sub, it was a fun but difficult challenge to stick close to the wall, which was not flat at all but full of sharp angles, curves, and overhangs. Big glass sponges seem to particularly like the overhangs, as did the big pink corals we saw the other day. We even saw one of those giant Antarctic isopods, which are so scary and horrible looking that they have become popular internet memes.

March 5, 2022

We arrived at our planned dive site to find it was covered in ice. This is not unusual, as a small shift in current or wind can quickly cause a previously clear bay to be filled with bergs of all sizes. It is one of our biggest challenges diving here. We don’t want to be diving in a place where we can get trapped under ice, of course, but we also have to worry about the damage even a smaller iceberg can do to the sub – and that includes the camera, the lights, the emergency beacon, and other somewhat delicate pieces of equipment attached to the outside. We have to worry about not just the conditions at the start of the dive, but at the end of it – which can be up to four hours later.

Our backup location for the morning was Vortex Island, a giant chunk of black rock that formed a fairly steep slope underwater. We stayed a bit shallower than usual, so we could surface quickly in case the ice started to close in on us. (Unlike SCUBA diving, where you have to come up slowly to avoid decompression injuries, the pressure does not change in the sub. We still need to be able to control our ascent, though, so we can avoid coming up under the ship – or, in this case, an iceberg.)

It was another pretty dive, with a high diversity and abundance of life. There were some very large glass sponges, including one that was so big that I had to back up the sub to fit the whole thing in the camera frame. I collected some truly strange specimens today. The giant sea spider had some parasites on it that are the stuff of nightmares. There was a mollusk that looked like a gelatinous glow in the dark tennis ball, a soft coral I hadn’t seen before, orange and yellow bryozoans, and a rock encrusted with things I can’t even offer any good guesses as to what they were.

The science team is happy.

In the afternoon, we went back to Corry Island, to survey a different part of the wall. It was as beautiful and full of life as what we found at the previous dive, adding more weight to our case that the area should be designated a Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem. We’ve been pretty focused on the science, so we’ve had a pair of indexing lasers on almost all the time to enable us to quantify the video data. For this dive, I was able to experiment a bit, and tried several long shots without lasers, just slowly moving along the wall. I hope it came out ok, because I really want to show people what it looks and feels like down there.

From the deck of the ship, we watched killer whales harass humpbacks and seals in an icy sea before a backdrop of tall black cliffs laced with frozen waterfalls escaping the glaciers above. Antarctica is… not like other places.

March 6, 2022

Sunday!

Today I dove with Roberto Garcia-Roa, a photographer with National Geographic. He is very humble, and was hesitant to dive if it was going to take an opportunity from someone else, or interfere with our research objectives. Roberto is here with Héctor Rodriguez, who is writing about the expedition for Nat Geo España. You can see their work here.

There are profiles of the team onboard, photos of the specimens we have collected, and images and stories of what we are seeing above and below the surface. Some of the content requires a free registration to access.

We dove in a canyon, and it felt a bit like a high risk / high reward option. Currents were pretty strong on the surface, so there was a chance they would just overpower the sub. And there were several glaciers in the area, which often means the bottom is silty and less diverse. But canyons are special places, and there is very little known about this one so we wanted to give it a shot.

It turned out to be a very steep slope with almost no silt, and extremely high abundance and diversity. The current wasn’t too bad, and the visibility was excellent. All that adds up to a great dive, with more than enough rationale to justify designation of a new Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem. We even saw a type of fish I don’t think we’ve come across before, bigger and fatter than an icefish. The lights on the sub attracted a small swarm of krill, and the fish skillfully darted in and out wolfing them down. I really hope we got it on video – as they say, pictures or it didn’t happen.

March 7, 2022

We stopped into a sheltered bay in the South Shetland Islands so we could do some quiet work at anchor. Everyone is happy with how much work we were able to do in Antarctic waters, and the feeling on board is relieved and relaxed as we wind down Antarctic sub operations and prepare to cross the Drake Passage. I’m starting to shift gears and get ready for the next leg of our submarine research dives: the Blue Hole, off the coast of Argentine Patagonia. More about that soon!

Meanwhile, the UN re-started negotiations for the Global Ocean Treaty in New York today, after a two year Covid hiatus. It’s possible they will finish up and adopt the treaty this month, but it is looking more likely that there will need to be another meeting in August. That gives us a few more months to build a movement that is too loud for them to ignore.

March 8, 2022

Now that our Antarctic dives are finished and we are heading back to Patagonia, I’d like to introduce you to my cabin mate, Florin Popescu.

We were both born in the same year – me in a small semi-rural New England town, and him in Communist Romania. We talked about our paths from where we grew up to being here on the ship.

There were a lot of times when his family went hungry, as even basic staples like milk and rice were often hard to come by. Electricity was a luxury, and very few people had cars. For Florin, the way out was the merchant marine. He studied to be an electrician, hoping to someday be a sailor.

When Florin was around 20, Romania’s dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu, had become so corrupt and hated that the people started to rise up despite the risk of being imprisoned or killed. The regime controlled the media, and most senior officers were Communist Party members, so the students at Florin’s academy only had rumors to go by. Ceaușescu tried to establish control with a televised speech in a public square in Bucharest. The students at the academy were told to watch on tv, but they’d had enough forced propaganda and were quietly dozing through the speech.

When the crowd in Bucharest drowned out Ceaușescu with boos and jeers, though, the students quickly realized that the rumors about resistance to the regime were true.

Once the protestors had stripped Ceaușescu of the illusion of omnipotence, his days were numbered. After a failed attempt to flee the country, the dictator was executed by firing squad on Christmas Day, 1989 – just four days after the disastrous public speech.

Florin’s first job as a sailor was on a ghost ship near Singapore. The vessel had run aground, and had a giant tear across its hull. Florin was essentially trapped on the ship for eight months, with dwindling food and water. Finally, the vessel owners stopped responding to the workers on the ship completely, and Florin returned home to Romania. From there, things eventually got a bit better, and he worked on a series of vessels, gaining experience and status along the way. He started working as an electrician on Greenpeace ships eleven years ago, where he has since met hundreds of crew members, volunteers, and Greenpeace campaign teams from all over the world.

Eventually, we came to share this cabin on the Arctic Sunrise, and to share our stories and views. It has been an honor and a pleasure to sail with him, and I will look forward to the next time.

March 9, 2022

We are nearly across the Drake Passage.

It’s been a long couple of days, even though the ship made good progress. The campaign team has gotten our sea legs at this point, so the crossing has been easier on all of us. Even so, the rolling was enough that we had to be careful to avoid getting tossed out of your bunks at night.

Tonight we anchor near Ushuaia, Argentina, where we will change over about 12 people and get ready to head out to the Blue Hole.

The waters around Antarctica are the only place on the high seas – areas beyond national jurisdiction – where there are any ocean sanctuaries today, and the only place with a regulatory body that has a mandate to create more. The Blue Hole is a different story. Like much of the high seas, it is largely unregulated. As a result, the Blue Hole has become a magnet for industrial fishing. Pirate fishing and human rights abuses are serious problems. Fleets from China, Korea, Europe and Taiwan bottom trawl for hake, jig for squid, and longline for Patagonian toothfish.

This is particularly concerning because the Blue Hole is also a biodiversity hotspot.

Upwelling carries high nutrient water up from the depths, feeding a rich ecosystem. Whales and dolphins migrate to the Blue Hole to feed and nurse their young. Humpbacks, blue whales, right whales, sei whales, fin whales and minkes can all be seen there, as well as orcas and other species of dolphins. Penguins, sea birds, and elephant seals also call the Blue Hole home.

We will be using the sub to survey the Blue Hole. Greenpeace visited the region in 2019 with an ROV, and documented considerable damage from bottom trawls. On this expedition, we hope to find undisturbed areas, so we can show policy makers why this vulnerable marine ecosystem deserves protection. It is also a particularly clear example of why we need a strong Global Ocean Treaty, which is being negotiated right now at the UN in New York.

March 9, 2022

We are nearly across the Drake Passage.

It’s been a long couple of days, even though the ship made good progress. The campaign team has gotten our sea legs at this point, so the crossing has been easier on all of us. Even so, the rolling was enough that we had to be careful to avoid getting tossed out of your bunks at night. Tonight we anchor near Ushuaia, Argentina, where we will change over about 12 people and get ready to head out to the Blue Hole.

The waters around Antarctica are the only place on the high seas – areas beyond national jurisdiction – where there are any ocean sanctuaries today, and the only place with a regulatory body that has a mandate to create more. The Blue Hole is a different story. Like much of the high seas, it is largely unregulated. As a result, the Blue Hole has become a magnet for industrial fishing. Pirate fishing and human rights abuses are serious problems.

Fleets from China, Korea, Europe and Taiwan bottom trawl for hake, jig for squid, and longline for Patagonian toothfish.

This is particularly concerning because the Blue Hole is also a biodiversity hotspot. Upwelling carries high nutrient water up from the depths, feeding a rich ecosystem. Whales and dolphins migrate to the Blue Hole to feed and nurse their young. Humpbacks, blue whales, right whales, sei whales, fin whales and minkes can all be seen there, as well as orcas and other species of dolphins. Penguins, sea birds, and elephant seals also call the Blue Hole home.

We will be using the sub to survey the Blue Hole. Greenpeace visited the region in 2019 with an ROV, and documented considerable damage from bottom trawls. On this expedition, we hope to find undisturbed areas, so we can show policy makers why this vulnerable marine ecosystem deserves protection. It is also a particularly clear example of why we need a strong Global Ocean Treaty, which is being negotiated right now at the UN in New York.

March 10, 2022

Florin and I went for a pretty epic hike this afternoon, through the town of Ushuaia and straight up a mountain.

We climbed over 1000 meters, the last 200 or so consisting of a mad scramble over/through loose chunks of rock. A typical exchange:

Florin (ahead of me, as usual): Should we abort? We should probably abort.

Me: You are probably right. This is a little crazy.

Florin (not moving): OK, let’s abort.

Me (also not moving): That makes sense.

Both of us crack up and keep climbing.

Maybe it wasn’t that smart, but the views were incredible. We watched a plane and a helicopter flying over Beagle Strait, far below us. The bright sun shone down on the town, and the water beyond. To the northwest, we gaped at the mountains beyond the mountains. After we’d finished drinking in the scenery from the top, we slid, surfed and stumbled our way back down, eventually reaching the tree line and entering a damp forest with wild looking lichens and colorful mushrooms. I am pretty sure my legs will be useless tomorrow, but after nearly a month at sea it sure felt great to get out and see some of Patagonia. It is easy to see why people are so attracted to this region.

March 11, 2022

We should probably talk about the discovery of The Endurance, the ship captained by Ernest Shackleton that was lost to Antarctic ice in 1915.

Any visitor to Antarctica likely knows the story: against incredible odds, Shackleton managed to get every member of the crew back home alive. This week, a team located the ship, sitting in remarkably good condition 10,000 feet down in the Weddell Sea. Finding and filming the wreck after it had been lost for over 100 years was an amazing feat, one that made us all feel a little more connected to these historic events.

As the discovery was announced while we were working in the same region, at times just a couple hundred miles from where the Endurance was found. This inevitably confused a lot of people, but our focus is on surveying and protecting marine life. Between locating the Endurance and the previous discovery of millions of icefish nests, it has been an amazing year in the Weddell Sea!

Today, we are loading on provisions and welcoming the South American team that will lead our exploration of the Blue Hole.

Our new science team is led by Martin Brogger, an expert on the animals living on the seafloor in this region, and Valeria Falabella, who has been studying the Blue Hole for ten years. We have the ship, the crew, and the equipment, and are ready to go. All we need now is some luck, in the form of seas calm enough for us to put the sub to work.

March 14, 2022

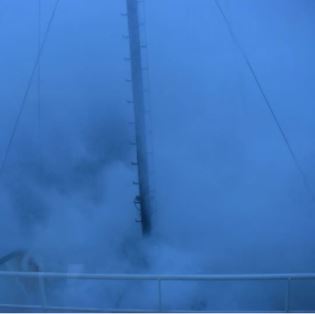

We left on the 12th, and sailed right into a storm (images from Barry Joubert).

Progress was very slow, often four knots and occasionally less than two. It wasn’t much fun for any of us, but it was especially hard for some of the people new to the “Washing Machine.” The captain declared Heavy Weather Conditions, meaning that the deck was off-limits, and we were all encouraged to move as little as possible.

Things have started to calm down a bit this afternoon, and we are now free (and able) to get back to normal. The salt air blowing in through an open door was delicious. So was lunch, the first full meal I had in a couple days. When people think of rough weather on a ship, they usually think of nausea and vomiting, but a lot of the time it just means not being able to do very much. On this ship, just walking to the lounge can be an adventure – and not the good kind.

My new cabin mate is another electrician – Ivan, from Bulgaria.

There is always an electrician or engineer in this cabin because it is set up with an alarm system so they can be reached right away if needed. It’s been mercifully quiet so far, but on some expeditions there are alarms almost every night. Ivan and I have sailed together before, but it has been quite a while. He has mostly been working on the Esperanza, which was just decommissioned. This is his first time on the Sunrise in nine years.

March 16, 2022

The waiting is the hardest part. We are here at the Blue Hole, and now we just need the seas to calm down a bit more so we can deploy and recover the sub safely. As you might guess, placing a somewhat fragile submarine with a couple somewhat fragile humans inside on the metal deck of a ship that is pitching and rolling can be a bit of a challenge. The next two days look pretty bad, so we are going to head for a more sheltered area and see if we can do some practice dives to get the science team fully ready to take advantage of the first suitable weather window we get.

This afternoon we have been using the ship’s sonar to map the northern canyons of the Blue Hole.

The bathymetric charts are ok, but lack the resolution we need to be sure what things actually look like down there. Sonar enables us to ground-truth the charts, and avoid wasting time later looking for the types of slopes and depth ranges we want.

While we were mapping the area, we were surrounded by fishing vessels the whole time. Valeria counted over 100 that she could see from the ship at one time. When you realize that we are 300 miles from the Argentinian coast, and that there is almost no regulation whatsoever for these vessels, it is clear that we have a serious problem. This is why we are here: to show the UN the kind of lawless concentration of fishing pressure that can occur on the high seas, in a biodiversity hot spot that has been largely unexplored. We are allowing vulnerable habitats to be destroyed before we even can guess what they look like, never mind how they function.

March 18, 2022

When we arrived at our sheltered bay yesterday, the wind was blowing 40 knots. The coast was rugged and barren, blasted clean by century after century of high winds and heavy seas. Even so, we were able to anchor, and do some training for new crew members and the science team. We practiced putting the empty sub in the water and putting it back on deck, both of which take just about everyone on the ship.

Once we felt comfortable with that, Valeria and I got in the sub and ran through pre-dive checks. Her excitement was contagious, especially when she told me about the times she had scuba dived in this bay and been visited by curious whales. I’ve done a lot of diving, but THAT is something I’ve never experienced. The deck crew released us from the crane, and we were in the water – free and off the ship for the first time since we left Ushuaia. It was a good feeling, and just a taste of what we hope is yet to come.

Tomorrow we will be back at the Blue Hole, where the forecast is not great but still better than anything we have seen there so far. We are running out of time and chances, but everyone is still staying positive. This quote that Rebecca Solnit shared from the Czech dissident and writer Vaclav Havel is on my mind: “hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something is worth doing no matter how it turns out.”

March 19, 2022

The captain declared Heavy Weather Conditions again last night during our transit back to the Blue Hole. I can’t say for sure how much of the last six weeks has been under HWC, but my bruises from being knocked around inside a metal ship are here to make sure I don’t forget. There have been several times where I was nearly thrown from my top bunk, but last night was the first time I almost fell out the long way. The only thing that prevented that is that the space between the bed and the wall is too small for me to land on the floor.

Too much swell for sub operations today. We did some work with the drop camera this afternoon, in the canyon we are hoping to dive tomorrow. The drop cam is not the most sophisticated tool; it is essentially what it sounds like – a video camera hanging on a cable attached to a winch so we can raise it and lower it as we view the camera feed on a monitor. The last time I used a drop cam, we lost it at the Amazon Reef when we hit a wall that did not show up on the bathymetric charts. This time we had a better idea of what to expect, since the ship has been using sonar to conduct surveys of the area.

We were having some luck with the drop cam, until we weren’t. Hopefully we can dive tomorrow.

March 20, 2022

It is more or less official: no dives are going to be possible at the Blue Hole this time. We were ready to go at 7 am, but the currents were strong and the swell was still pretty formidable. We tried again at 10, but the wind we’d been expecting had started picking up. A storm is on the way, so it looks like that’s it. Very disappointing.

If you want to make a difference, first you have to show up.

We showed up, in a big way. But that isn’t always – or even usually – enough. That leads to the next most important thing, which is that you can’t give up just because things don’t go your way sometimes. The Argentinian team is just getting started, with some very powerful work planned over the next few weeks that you may well see in the news at some point.