In April 2016, many members of the public were amazed by the announcement of a gigantic new coral reef system in an unlikely place: at the mouth of the Amazon River.

The reef is 3,668 square miles, and it goes from the border between Brazil and French Guiana to the Maranhão state. The first of its kind, scientists are calling it one of the most important discoveries in marine ecology of the last decades.

But this ecosystem is already under threat. The region where the Amazon River meets the Atlantic Ocean is also being seen as the next frontier of offshore oil exploration. Three different oil companies plan to start exploring there in the first half of 2017.

Marine biologist and Greenpeace US Oceans Campaign Director John Hocevar has traveled down to Brazil to join the crew of the Esperanza and a group of researchers who have set out to document this amazing natural wonder for the very first time. He’ll be sharing Notes from the Field as he goes.

Sat, Jan 21, 2017

I am headed to Brazil to board the Esperanza for three weeks. We will be working with a team of Brazilian scientists, using a small research submarine to explore a newly discovered reef for the first time. Best part: I will be piloting the submarine! Worst part: BP, Total, and a Brazilian oil company want to drill in the area. We don’t even know what’s down there, and it is already at risk. Hopefully, what we find in this expedition will make the Brazilian government reject these oil companies’ plans.

From Your Faithful Editor: The photo above of John was taken while he was part of a team conducting aerial assessment of environmental impacts of the Hurricane Rita in the Gulf of Mexico and coastal areas of Louisiana and Texas. This is not how he traveled to Brazil.

Interestingly enough, John would return to this region a few years later to pilot a Dual Deep Worker submarine to support the work of scientists and researchers who were using Greenpeace’s Arctic Sunrise to investigate the aftermath of the tragic BP oil disaster.

And, let’s face it, this is a much more interesting photograph than one of John during his 12-hour layover in Brasilia on his way to the ship.

Sun, Jan 22, 2017

When I studied coral reef ecology in grad school back in the early 90s, we were taught that the Amazon was an ecological boundary. There were corals to the north, and corals to the south, but no real mixing of the two. Last year, Brazilian researchers published the surprising finding that there is actually a giant reef UNDER the plume of the Amazon, several miles offshore. What?!? Surely, no sunlight can get down there, so how is this possible? What lives there? Is this a whole new type of ecosystem, or biome? We are going to find out!

Mon, Jan 23, 2017

We are in the port of Santana, at the mouth of the Amazon. I shared my morning tea with leaping dolphins and flocks of squawky parakeets. I love the tropics – everywhere I look I am surrounded by an incredible abundance of plants, birds, frogs, and insects.

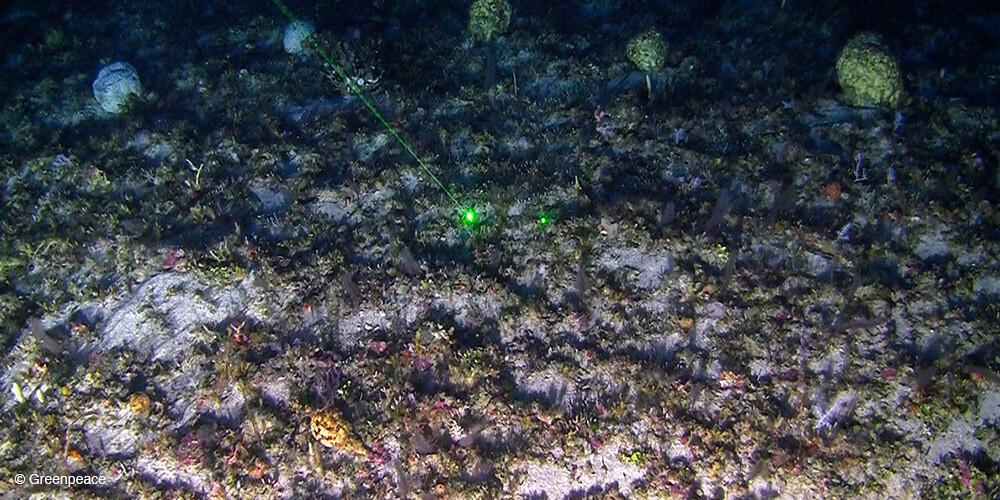

Today we are working on our sub dive plans with the Brazilian scientists. We are sharing images from our work in the Bering Sea canyons, the Arctic, and the Gulf of Mexico, and they are telling us some of the things we might encounter here. Fabiano was telling us about rhodoliths, the foundation of a whole ecosystem that is little understood even by most marine biologists. Picture huge plains of pink tennis ball-sized “stones” which are actually miniature worlds full of tiny invertebrates, algae, bacteria, and larval organisms. They are found in such huge numbers that they eventually form massive reefs so large that they may play important roles in our planet’s carbon cycle. I have a feeling I will be saying more about these guys later, so if I didn’t lose you at bacteria and larval organisms stand by for more.

The Crew

It is great to see so many familiar faces from past voyages to the Arctic, Chile, the Mediterranean, and the Gulf of Mexico. Greenpeace ships are run by a dedicated and highly professional crew, and they come from all over the world. Our crew right now come from eighteen different countries, including a violin-playing Korean, a Filipino that can play flawless darts even when the ship is rolling in a storm and a Belgian author who is also my fellow submarine pilot. Our captain, Joel, is an American who lives in Washington and has spent much of his life working on boats in Alaska.

The Ship

Launched in February 2002, the Esperanza is the largest vessel in the Greenpeace fleet. Esperanza – Spanish for “hope” – is the first Greenpeace ship to be named by our supporters. At 72 meters in length, and a top speed of 16 knots, the ship is ideal for fast and long range work. Its ice class status means it can also work in Polar Regions.

You can follow the travels of the Esperanza and all our ships through their live webcams.

Tues, Jan 24, 2017

From Your Faithful Editor: So, this morning I opened my phone to find a message from John titled “Bugstravaganza,” which, in addition to saying he was on his way to board the ship, included an image of what looked like the thing people in the South politely refer to as a Palmetto bug. A man’s shoe was placed beside it for scale.

It was not small.

So, instead, here is a photo of a Black Bearded Saki taken by José Caldas. You’re welcome.

Wed, Jan 25, 2017

Today I got reacquainted with the sub, and worked with the scientists and the sub team to get us ready to dive tomorrow. We are out in the open ocean now, and the water is starting to look much clearer. A bunch of took a break this afternoon to watch dolphins chase flying fish – not a bad day at the office. We will be on our first dive site early in the morning, and are all set to go.

Thur, Jan 26, 2017

Dr. Ronaldo Francini-Filho and I are getting ready to dive. He is getting familiar with the lung-powered scrubbers, an emergency system we can use to stay on the bottom for up to 72 hours without power. The fact that it makes us look like Jedi fighter pilots makes it easier to think about.

Really, though, the subs are very safe, with numerous backup systems. We even have a rescue sub waiting on deck if needed.

Our biggest concern is the possibility that we could get tangled in abandoned fishing gear.

The conditions look better than we could have ever hoped for – close to 75 feet of visibility and relatively calm seas. If all goes well, the next thing I share with you will be the story of the first dive on this newly discovered reef.

Day of the Drop Cam

Everything is ready, so now we are just waiting on the weather to calm down a little.

To make good use of our time and to maximize our chance of success, we are using the ship’s sonar and a drop cam to learn as much as we can about our potential dive sites before we take the sub down there.

In these waters, the charts are not very accurate. What looks like a seamount that comes up to within 65 feet of the surface may or may not actually exist, and there’s no way to know for sure without going there ourselves.

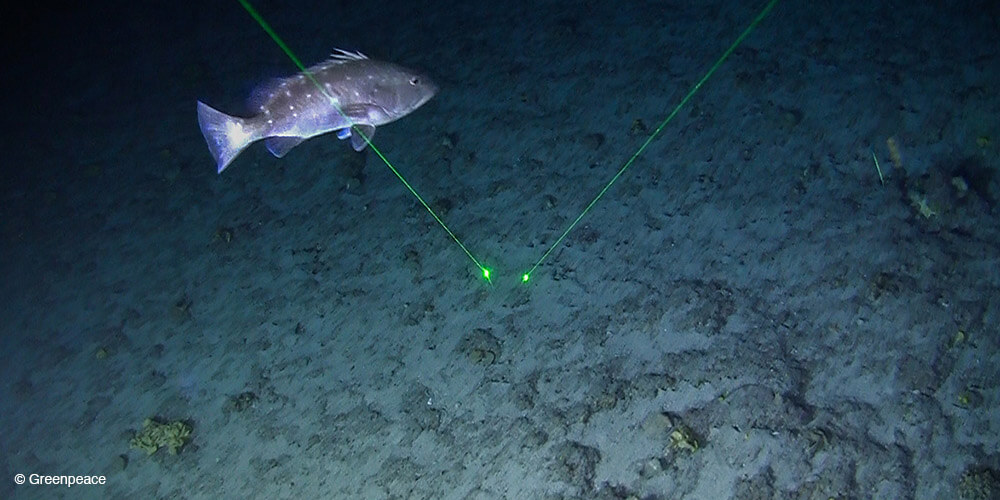

The thing I love about the drop cam is that everyone can see what is happening on the monitor in real time. We had half the ship gathered around the screen as these sponges, corals, fish and, yes, rhodoliths of the Amazon reef were seen by human eyes for the first time. In one 45 second sweep, the scientists saw three different things that were not previously recorded here.

Fri, Jan 27, 2017

This morning we made the first dives in history on the Amazon Reef. Joining me in the submarine was Dr. Ronaldo Francini-Filho, a renowned coral reef ecologist from Sao Paulo. We touched down on a sandy bottom at about 675 feet, and gradually moved up slope. We passed over a really strange mound covered in yellow sponges, and a ledge that I later learned had been formed when it was on the coast 18,000 years ago and sea level was lower. It is helpful to have a marine geologist on board!

As we reached 492 feet, we entered the mesophotic zone, where enough sunlight reaches from the surface to allow plants to survive.

Here we started to see lots of black corals, which are actually mint green, and dense fields of sponges. We will need to look at the video to be sure, but it looked like there were thousands and thousands of soft corals, providing habitat for countless juvenile fish. At a depth of 260 feet, we watched surgeonfish line up to have their parasites removed by wrasses at a cleaning station. Perhaps most exciting, Ronaldo thinks two of the butterfly fish we documented may be new species.

If the weather cooperates, we will have a chance to do quite a bit more diving out here. But in case we never get to do another dive, let me say this: The Amazon Reef is no place to drill for oil. It is unique and full of life, and should not be for sale to oil companies like BP, Petrobras and Total.

Sat, Jan 28, 2017

From Your Faithful Editor: If you knew me in high school, you would know that science was not at the top of my list of favorite subjects. Now, many, many (many, many) years later, I would like all of my science teachers to know that the slide show below, which includes some of the first images from the Amazon Reef, made my entire day.

Sat, Jan 28th – Part II

We got in two excellent dives today. Kenneth brought down Dr. Fabiano Thompson, and I brought Ian Urbina, author of the “Outlaw Ocean” series for The New York Times. Visibility was very good, and we got the best images yet of this regional biodiversity hot spot.

My favorite parts are the large rhodolith mounds carefully assembled by fish, which attract dozens of colorful wrasses, angelfish, damselfish, triggerfish, parrotfish, squirrelfish, and more, along with invertebrates like peppermint shrimp, brittle stars, and arrow crabs.

For most of our dives, we are moving on a constant heading and speed, using the video camera, indexing lasers and four banks of LED lights to collect video data that can be processed and quantified so the scientists can determine the biomass, species composition, density and diversity of marine life. When we see things that look particularly interesting, we can pause our transects and zoom in for a closer look. In the flatter areas of the reef, these rhodolith mounds stand out like highrise hotels, with fish in each room and hallway.

Sun, Jan 29, 2017

We came close, getting as far as putting people in the subs on deck, getting the rescue boat in the water and having Erick standing by on the crane, but the sea conditions were a bit too rough for us to get in any sub dives today. If we get waves much more than 4 feet high, it gets harder for the crew to safely put the sub back on the metal deck of the ship. We use three tag lines along with the crane to keep the sub from swinging around too much, which works well. Greenpeace crews are very comfortable loading and unloading heavy objects – we deploy our inflatable boats in fairly rough seas all the time – so things go pretty smoothly even when the ship is rolling around a bit.

Since we couldn’t use the subs, Texas (our Radio Officer) got the drop cam fixed up and we did a few surveys with that throughout the day and into the evening. The highlight was after it got dark, when the lights attracted a school of fish. As everyone watched the fish swim around the bright lights, a small shark darted in and ate one. Nature!

Mon, Jan 30, 2017

The forecast wasn’t great for today, so I wasn’t expecting much when I walked out on deck at 6:30. We decided to prep the subs for launch anyway, in case the conditions became stable enough to launch.

By 7:15, we were on the crane, up in the air and over the side. Texas swam over and released us from the crane, and down we went. We landed on a vast undersea desert plane, with waves of sand stretching out around us as far as we could see – which wasn’t really all that far.

Unlike our previous dives, this time there was a lot of particulate matter in the water, known as “marine snow.”

As a biologist, I am always hoping for the fish, corals, sponges and other creatures we might find on a reef, but even this dive tells the science team important things about the overall system. Closer to the shore than the reef, these sand flats are formed into ridges by very strong tidal currents that keep any living things from establishing themselves on the bottom.

Now we are heading into deeper water, to visit another part of the reef we have not yet explored.

Mon, Jan 30 – Part II

Our second dive was one of the most spectacular so far. We dropped down onto a steep wall full of life, with schools of fish large and small. The current was too strong for the sub’s thrusters to handle, but before we left the area we got footage of a fish that appeared to be a grouper but was so unusual the scientists are not yet sure even what genus it might belong to. As if that wasn’t enough, a manta ray swam right up to the domes of the sub before soaring gracefully onward. Amazing.

From Your Faithful Editor: Just a quick note that this is not a photo of the fish John mentioned in his post. Please know that we’re sharing new photos as soon as they are available which, considering these folks are on a ship floating around above a reef no one has explored before, is faster than you’d think, right?

Belém

Today we are heading to Belém, the largest city near the Amazon mouth and a thriving regional hub. We will have one day here to changeover some crew before heading back out to sea for the second leg of our expedition. We will be saying goodbye to two of the Brazilian scientists, three journalists, and several Greenpeace crew. Saying goodbye will be bittersweet for most of them, as they will be returning to families and conveniences they have missed but leaving their adopted Esperanza family behind.

If weather permits, we will attempt to document the northern sector of the reef for the first time.

The odds are against us, as this portion of the reef is currently under the plume of the Amazon. That creates a host of new challenges for us.

First, we may have to battle strong currents, particularly from the Amazon itself, but also from tidal currents. It may also be difficult to adjust the buoyancy of the sub appropriately, because our buoyancy will be very different in the freshwater lens at the surface than in the saltier water we expect to find at depth. And our biggest question is whether we will be able to see anything at all, or if the silt carried by the Amazon will make the water even near the seafloor too cloudy to dive safely (or document anything with the sub’s video camera).

For now, I am excited to have a day to explore a new city and walk around on dry land – and for what we may find next week, when our submarine exploration of the Amazon Reef continues.

Sub Socks?

Q: How much space is there in the sub for you and your passenger?

The space in the sub is very, very small – to the point where if I turn my shoulders to try to look behind me I am probably going to knock something over.

The pilot and passenger are isolated from each other in two self contained sections. We can see each other, and talk to each other over a radio, but we’re each somewhat on our own.

Q: Is there special clothing you wear in the sub?

No, but we can’t wear shoes, so we recommend wearing warm socks or slippers. Even if it’s warm on the surface, it can still get cool and even cold at depth after a while. Mostly people wear clothing they can be comfortable sitting in for two to four hours.

Thur, Feb 2, 2017

Our business in port taken care of, we are leaving Belém for the second leg of our research expedition.

It is an auspicious day to head back out to sea, as this is the day Brazil honors Yemanja, the Goddess of the Sea. One of seven Yoruban deities, Yamanja is also the spirit of moonlight and the patron of fishermen.

It will take us until tomorrow evening to arrive at our next dive site, so if the weather cooperates we will put the sub back in the water again on Saturday morning.

Fri, Feb 3, 2017

After a day and a half steaming north from Belém, we arrived at our next dive site last night.

At 6:00 this morning, we put in the drop cam to see what the habitat, visibility and currents look like here, and began running the sub through pre-dive checks. Unfortunately, an intermittent issue we’ve had with the sub’s control power resetting went from intermittent to shut down completely, so we are on hold for now.

The team is working on repairing the problem which Jeff, the Dive Supervisor, referred to as “not heart surgery, but kidney surgery.” I’ve seen these guys solve some pretty daunting challenges over the years, so I’m optimistic we’ll be back on the reef soon.

It has been great to see this expedition start to get some major media coverage, with solid stories published all over the world.

Policy makers in Brazil are paying attention, as are the oil companies that had planned to start drilling here soon. Over 300,000 people have joined the campaign already, which continues to grow each day.

On Thursday, Chelsea Clinton tweeted about the reef:

Breathtaking coral reef discovered in an unlikely spot: the Amazon! Hope all necessary actions taken to preserve it: https://t.co/GSUzsv2uXy

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) February 1, 2017

Sat, Feb 4, 2017

The sub ops team replaced the power supply and tested it for an hour this morning with no glitches, so we were cleared for our first dive of the second leg of the Amazon Reef expedition. Kenneth and Ronaldo ran through pre-dive checks with no problems, and proceeded with their dive. Within five minutes of landing on the bottom, they had already seen two species that we haven’t encountered before here. Unfortunately, the power shut down again, and they had to abort the dive.

The sub is very safe, with back ups on top of back ups, so even if three or four things go wrong we are still in good shape.

The danger is not so much to our safety, but to the expedition itself – that something will break that we are unable to fix. If that happens, we are too far out to sea at this point to be able to continue diving.

A Special Note from John

Our thoughts today are partly with the family of Rob Stewart, the director of Sharkwater and a friend to several of us on board. Rob’s body was found yesterday after he went missing during a dive looking for rare sawfish sharks near Key Largo. He did a great deal to raise awareness about shark finning, and the fact that sharks are worth more to us alive than dead.

From Your Faithful Editor: The photo above is of a group of Silky sharks circling a fish aggregating device (or FAD) in international waters in the Indian Ocean. The marine snare was documented by the crew of the Esperanza during an expedition in the spring of 2016.

Mon, Feb 6, 2017

The sub is still out of commission due to a problem with its electronics. The sub operations team is working long hours to fix it, and in the meantime the rest of the crew is doing our best to make good use of the down time.

We are deploying the drop cam and a CTD to collect oceanographic data along the reef, and to identify areas to visit with the sub when we are able to get back in the water.

There continues to be a lot of media interest, so some of the team is still busy with processing images, creating video content, and doing interviews.

In the evenings, we’ve been watching Breaking Bad and playing darts – which can be pretty entertaining on a rolling ship.

From Your Faithful Editor: The portrait of German Oceans Campaigner and coral expert Sandra Schoettner was taken by Marizilda Cruppe.

Rough Seas

Well, we think the sub is fixed, but the seas are too rough to find out for sure. Hopefully we will be able to dive tomorrow, which is our last chance before we have to head back into port.

From Your Faithful Editor: Portrait of Brazilian scientist Ronaldo Bastos Francini Filho from the Federal University of Paraíba on the Esperanza by Marizilda Cruppe.

Thur, Feb 9, 2017

The second leg of our expedition was limited to one short dive, due to a combination of very large waves and some technical problems with the sub.

Fortunately, the first leg was so productive that the expedition had already exceeded expectations by our third day.

The scientists told reporters that by the end of the first dive, they had learned so much new information about the Amazon Reef that their landmark paper in Science was obsolete.

The images we got with the subs appeared in favorable coverage in some of the world’s largest and most influential media outlets, and helped 23 offices engage over 400,000 people in support of the campaign.

On a personal level, it was an amazing experience to see the Amazon Reef first hand, and to work with such a fantastic team on board as well as supporting us back on land. We will spend the next day as we head back into port debriefing and expanding our plans to build on the momentum we have sparked with this expedition.

Fri, Feb 10, 2017

The old charts lacked our global understanding of the planet, and areas beyond where anyone had traveled and lived to tell the tale were often illustrated with sea monsters or dragons. Even today, with state of the art navigational equipment and charts based on extensive soundings, there are giant gaps and inaccuracies in what we think we know about the sea floor. Over the last two weeks, we have regularly visited flat areas that appeared as seamounts on the charts, or dramatic features that didn’t show up on the charts at all. Today, one of those inaccuracies nailed us good.

On our last dive day, it was too rough to put the sub in the water so we were using the drop cam one last time before we headed back toward Belem.

We watched the monitor as we reached bottom, which was nothing but sand as far as we could see. After towing the drop cam for several hundred yards with no change in the habitat, we decided to pull it back up. It started to look a little more interesting as we came upslope, but nothing prepared us for the giant pile of boulders that came out of nowhere.

According to the chart, there was nothing there but flat deep bottom, but these boulders were very real – real enough to batter and ensnare the drop cam, which will lie on the bottom in hopes of being recovered on a future expedition. We reeled in the cable hoping to find at least part of the drop cam intact, but when we reached the end there was nothing but sheered off cable.

Time to call it a day, and head back to Belem with the huge store of images and data we gathered throughout the expedition, and let the scientists begin the painstaking work of analyzing it all.